Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is the most abundant molecule found in the body after water. It is most known for its involvement in converting foods into energy, but it also involved in repairing DNA damage and is thought to be relied upon by more than 300 enzymes. NAD is a crucial molecule for healthy aging.

The body can create NAD from our diet. However, factors such as aging, high alcohol consumption, overeating, high blood sugar and insulin levels, and DNA damage deplete NAD levels and it can be difficult for the body to regenerate adequate supplies.

Low NAD levels make the visible signs of aging more noticeable and leave you more likely to develop chronic diseases, such as heart disease, diabetes and Alzheimer’s dementia.

By middle age, our NAD levels have depleted to around 50% of the levels you had in your youth. Boosting NAD levels can reduce insulin resistance, improve the health of mitochondria and help us to live healthier for longer¹.

What are NMN and NR?

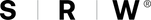

Two of the most popular supplements for replenishing NAD+ levels are two of its natural precursors, Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN) and Nicotinamide Riboside (NR).

These molecules are found in the body and are used to create healthy NAD levels.

Your body is constantly converting the foods that we eat into molecules that can be recognised and used to build molecules that can be used for different functions processes in the body.

In the case of NAD, the body is able to create it using three pathways. The De Novo pathway converts tryptophan into NAD. The Preiss–Handler pathway uses dietary nicotinic acid, from Vitamin B3, into NAD. The salvage pathway uses nicotimamide riboside (NR), also found in Vitamin B3, into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and then into NAD. This pathway can also recycle NAD to be used by the body again.

As shown in the below diagram, to do this the body converts the dietary sources of vitamin B3 and tryptophan into NAD via several steps, each of which rely on enzymes (e.g. NAPRT, NRK, etc) to convert each molecule to the next in the pathway. However, dietary sources are insufficient to replenish NAD levels as we age.

- Tryptophan can be found in foods such as turkey, oats, nuts and seeds.

- NMN can be found in fruits and vegetables such as avocados, brocolli, cabbage, edamame and cucumbers1.

- NR can be found in foods such as brewers yeast.

What is the difference between NR and NMN?

What is the difference between NR and NMN?

NR and NMN are similar molecules found at different stages in the NAD salvage pathway (see above). One of the key differences is the structure of these molecules, NMN contains a phosphate group and is therefore a slightly larger molecule.

Until recently, it was thought that supplementary NMN was too large to effectively enter cells and that the body must first have to convert it back to NR for it to be used in the body. Some suggested that because of this pathway, NR was a more efficient NAD+ boosting precursor.

However, recent research has now discovered a gene called Slc12a8, which creates a specific NMN transporter that carries NMN through the cell membrane so that it can be directly absorbed into the cell². As the NMN molecule is easier for the body to convert into NAD, due to less conversion requirements, it is now thought that NMN is more stable than NR¹.

Therefore, although both molecules can raise NAD levels, NMN is now becoming the preferred choice. NMN is the more stable molecule and the body can more easily convert it into NAD.

Suzy Walsh

BBA (Hons)., BNat., mNMHNZ

Registered Naturopath & Medical Herbalist

References:

¹Shade, C. (2020). The Science Behind NMN – A Stable, Reliable NAD+ Activator and Anti-Aging Molecule. Integrative Medicine, 19(1). PMC7238909.

²Grozio, A., Mills, K. F., Yoshino, J., Bruzzone, S., Sociali, G., Tokizane, K., Lei, H. C., Cunningham, R., Sasaki, Y., Migaud, M. E., & Imai, S. (2019). Slc12a8 is a nicotinamide mononucleotide transporter. Nature Metabolism, 1(1), 47-57. doi:10.1038/s42255-018-0009-4

![Never Grow Old - Longevity Issue [Nutrition Business Journal]](http://scienceresearchwellness.com/cdn/shop/articles/NBJ_Post_-_LinkedIn.jpg?v=1692742979&width=1500)

![Circulatory system care "vital" [NZHERALD]](http://scienceresearchwellness.com/cdn/shop/articles/SRW_-_News_Clip_-_Post_-_Cir1_-_D1_dfadc7dc-c57a-4f80-82bd-4fdb5ba5f0cd.jpg?v=1692742734&width=1500)